Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Res Community Public Health Nurs > Volume 35(1); 2024 > Article

-

Review Article

- Optimistic bias: Concept analysis

-

Miseon Shin1

, Juae Jeong1

, Juae Jeong1

-

Research in Community and Public Health Nursing 2024;35(1):112-123.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.12799/rcphn.2023.00360

Published online: March 29, 2024

1Doctoral Student, Department of Nursing, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju, Korea

- Corresponding author: Miseon Shin Department of Nursing, Jeonbuk National University, 567 Baekje-daero, Deokjin-gu, Jeonju 54896, Korea Tel: +82-63-270-3116, Fax: +82-63-270-3127, E-mail: sms207111@naver.com

© 2024 Korean Academy of Community Health Nursing

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivs License. (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0) which allows readers to disseminate and reuse the article, as well as share and reuse the scientific material. It does not permit the creation of derivative works without specific permission.

- 583 Views

- 8 Download

Abstract

-

Purpose

- The purpose of this study was to analyze and clarify the concept of ‘optimistic bias.’

-

Methods

- A review of the literature was conducted using several databases. The databases were searched using the following keywords: optimistic bias, optimism bias, and concept analysis. The literature on optimistic bias was reviewed using the framework of Walker and Avant’s conceptual analysis process.

-

Results

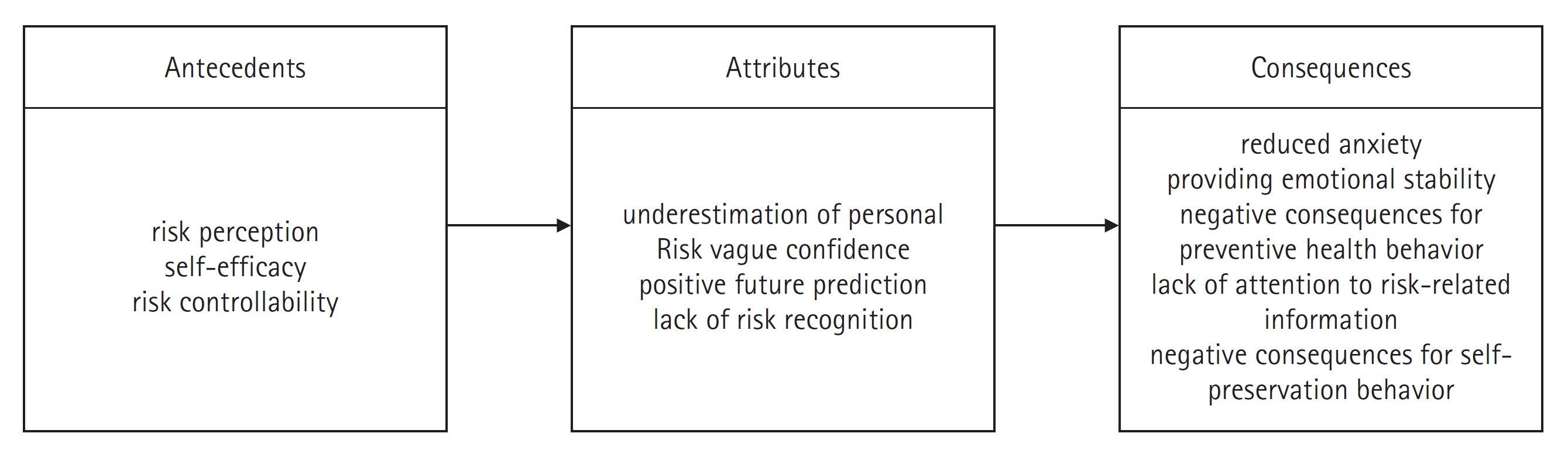

- Optimistic bias can be defined by the following attributes: 1) underestimation of personal risk, 2) vague confidence, 3) positive future prediction and 4) lack of risk recognition. The antecedents of optimistic bias are as follows: 1) risk perception, 2) self-efficacy, and 3) risk controllability. The consequences of optimistic bias are as follows: 1) reduced anxiety, 2) providing emotional stability, 3) negative consequences for preventive health behavior, 4) lack of attention to risk-related information, and 5) negative consequences for self-protection behavior.

-

Conclusion

- The definition and attributes of optimistic bias identified by this study can provide a common understanding of this concept and help to develop a nursing intervention program effective in preventing, protecting, and improving health of subjects in the field of nursing practice.

- 1. Background

- Chronic diseases are illnesses with a very high disease burden, and they are reported to account for 80% of all deaths and 41% of medical expenses in Korea [1]. Chronic diseases are one of the leading causes of death worldwide [2], and in Korea, the prevalence rates of chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and hyperlipidemia have been gradually increasing [3]. In addition, mortality rates due to chronic diseases have been continuously increasing, and this problem has become one of the important considerations in national health management and establishment of public health policies [4]. As such, chronic diseases are currently the most difficult task in healthcare, and both individual and societal efforts are needed to prevent chronic diseases [5].

- In terms of the concept of disease prevention, the concept of optimistic bias acts as an important factor [6]. Optimism bias means the psychological tendency for individuals to underestimate their risks or likelihood to experience negative future events but overestimate their likelihood to experience positive future events, and it generally refers to the tendency to underestimate one’s chances of experiencing unfortunate events or diseases and overestimate one’s probability of experiencing positive events [7]. When individuals have optimistic bias, they tend to make more optimistic judgements about their own situations than others’ situations [8]. Optimism bias may cause people to think lightly of health-related risks and may also affect the way patients follow treatment plans [7]. Optimism bias is also related to mental health. An optimistic attitude may be helpful for stress management, but unrealistic positive expectations may lead to disappointment or anxiety [8].

- In relation to disease prevention, optimistic bias has a significant impact on disease prevention. This bias has been shown to affect the way individuals perceive and respond to health-related risks [6]. In addition, optimistic bias is an important factor in the design and implementation of various public disease prevention campaigns and health promotion programs. A prior study reported that optimistic bias enhances motivation for taking preventive measures against the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), and the study suggested that it is important to emphasize actual risks in order to reduce optimistic bias and promote participation in preventive behaviors [9]. In addition, a study on the relationship between optimistic bias and smoking found that smokers tend to overestimate the effectiveness of their preventive behaviors [10].

- With respect to disease management, optimistic bias has also been shown to influence the occurrence, spread, and management of diseases, and thus in terms of disease management, it is important to consider optimistic bias in order to change individuals’ behaviors and promote preventive measures [7]. A survey study on the perception of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and optimistic bias among male smokers suggested that it is important to change the perception and attitudes of the target group for the prevention and management of COPD, and that customized education programs and public health campaigns are needed to induce such changes [11]. If optimistic bias is not taken into account, in terms of the development and implementation of strategies for disease prevention and management, unrealistic expectations and inaccurate evaluations may hinder adequate implementation of effective preventive and management measures, and unpredictable problems may arise in disease transmission and management [12].

- The above findings show that it is very important to understand how optimistic bias affects disease management and prevention. If individuals underestimate the risks of their behaviors that may have a harmful effect on their health, this underestimation of risks may hinder their adoption and maintenance of healthy lifestyle habits, which in turn may have a negative impact on the prevention and management of diseases [7].

- This concept of optimistic bias has been considered in diverse health areas such as HIV, smoking, heart disease, skin cancer, and chronic diseases [13]. A review of previous studies showed that research on optimistic bias has been conducted in various health-related fields such as cancer [14,15], AIDS [16-18], stroke [19], and COVID-19 [20-22]. A number of previous studies have demonstrated that optimistic bias affects health behaviors in relation to the perception of health risks. In connection with disease prevention, research findings suggest that there is a need to consider the degree to which individuals with optimistic bias will perform desirable disease prevention behaviors actively.

- Therefore, an accurate understanding of optimistic bias will make an important contribution to improving strategies for disease prevention and management. In this respect, the present study is expected to contribute to providing a deeper understanding of this phenomenon and exploring more effective approaches to disease prevention and management. In addition, it is thought that effective disease-related nursing interventions in nursing practice necessitates an accurate understanding of the concept of optimistic bias held by the recipients of nursing care. Therefore, this study aimed to identify and define the attributes of optimistic bias through a conceptual analysis of optimistic bias about illness that has been studied in various fields.

- 2. Purpose

- The purpose of this study was to present a theoretical basis for the concept of optimistic bias in nursing care recipients by clearly identifying the attributes of optimistic bias. In other words, this study aimed to conduct the concept analysis of optimistic bias based on the conceptual analysis framework presented by Walker & Avant [23], understand the optimistic bias of nursing care recipients, and provide basic data for the development of effective nursing interventions in nursing practice. The specific objectives of this study are as follows:

- 1) To define the concept of optimism bias;

- 2) to understand the uses of the concept of optimistic bias through a literature review;

- 3) to identify the attributes of optimistic bias and describe a model case based on the identified attributes;

- 4) to identify the antecedents and consequences of optimistic bias.

Introduction

- 1. Study design

- This study is a concept analysis research that applied the method of concept analysis proposed by Walker & Avant [23] to derive the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of the concept of optimistic bias. The specific procedures of concept analysis are as follows:

- 1) Select a concept; 2) Set the purpose of concept analysis; 3) Identify all the uses of the concept; 4) Determine the defining attributes; 5) Present a model case; 6) Present additional cases (borderline cases, contrary cases, and related cases); 7) Identify the antecedents and consequences of the concept; 8) Define empirical referents.

- 2. Subjects

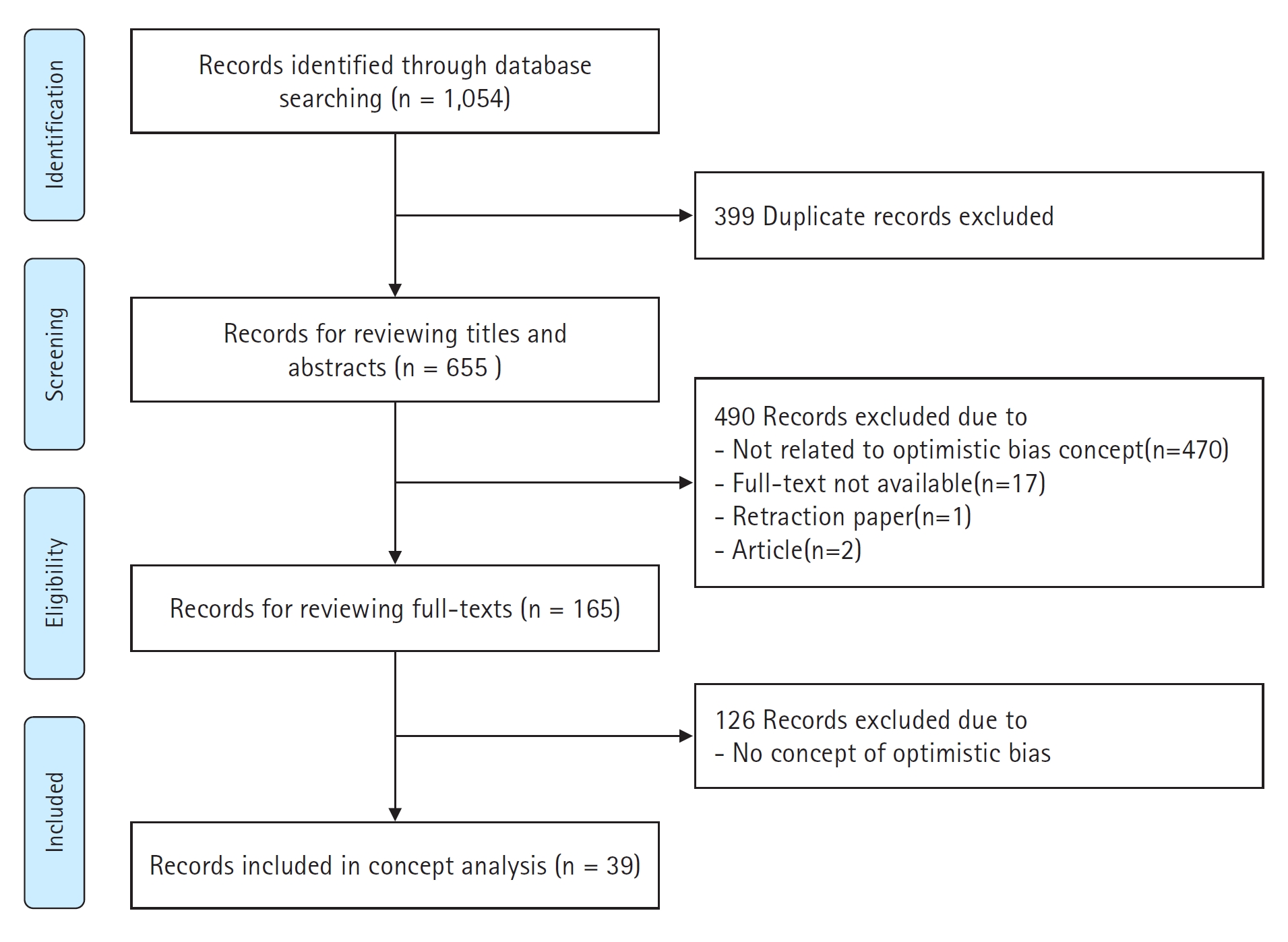

- Through literature search using domestic and foreign electronic databases and the review of papers retrieved through the search, 19 papers were finally selected for analysis (Figure 1).

- 3. Ethical considerations and preparations of the researcher

- This study aimed to investigate the attributes, causes, and consequences of optimistic bias through text data analysis using previously published research papers available through academic databases. It was confirmed prior to this research that this study was exempt from IRB review because personally identifiable information, such as personal ID, was not collected or used in the process of text data analysis.

- The researcher is a doctoral student who has completed a course on nursing theory development related to concept analysis, and the researcher continuously reviewed related academic professional books and research papers from various perspectives during the research process. In addition, in order to apply the method of concept analysis proposed by Walker & Avant [16], the researcher meticulously reviewed previous studies that applied the analysis method, and conducted this study through continuous discussions with the professor in charge of the relevant course.

- 4. Data collection and analysis

- The literature search for this study was carried out from March 15 to May 17, 2023, and it was conducted using domestic and international electronic academic databases. No search limit about the publication date was set in order to use abundant data. The keywords used in the literature search using electronic databases were as follows (Table 1).

- The search of foreign studies was conducted using Publisher MEDline (Pubmed) and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The search terms used were ‘optimism bias’ and ‘optimistic bias’, and a total of 618 articles were retrieved. Out of the 618 articles, 128 duplicate articles were removed. In addition, 17 papers whose full texts were not available, a retracted article, and two other articles were excluded. Additionally, 354 papers not related to the concept of optimistic bias were also excluded. As a result, the full texts of a total of 116 articles were reviewed.

- The search of domestic studies was conducted through the Korean Studies Information Service System (KISS) and Research Information Sharing Service (RISS), and the used search terms were Korean words for ‘optimism bias’, ‘optimistic bias’, ‘optimism prejudice’, and ‘optimistic prejudice.’ A total of 436 articles were retrieved, and among them, 271 duplicate articles were excluded. 116 articles not related to the concept of optimistic bias were initially excluded, and the full texts of a total of 49 articles were reviewed.

- In short, a total of 165 articles including domestic and foreign studies were initially selected, and after reviewing their full texts, 146 papers that did not deal with the concept of optimistic bias were excluded, and a total of 19 articles were selected for final analysis (Figure 1).

Methods

- 1. Literature review on the concept of optimistic bias

- The National Institute of the Korean Language defines ‘optimistic’ as viewing one’s life or things from a bright and hopeful perspective and ‘bias’ as the quality of being biased toward or against a certain side. Therefore, since optimistic bias is a term made by combining the word ‘optimistic’, which means viewing things from a bright and hopeful viewpoint, and the word ‘bias’, which means being biased to one side, it can be defined as the tendency to view things from a perspective biased toward the bright and hopeful side of things [24].

- The concept of optimistic bias was first described and demonstrated by psychologist Neil Weinstein in 1980, and various studies on the concept have since been conducted in the field of psychology. In psychological research, the concept of optimistic bias has been studied as a moderator variable for specific behaviors [25]. Factors affecting optimistic bias presented in literature are generally not demographic characteristics but psychological factors related to perception or disposition, such as individuals’ general positivity bias, individuals’ risk perception, egocentric way of thinking, self-efficacy, involvement based on experience, inspiration, illusion of control, social distance, and risk recognition [26]. This concept has also been studied from a perspective related to media, and it has been suggested that the concept of optimistic bias can be viewed as a result of media use [8]. In addition, optimistic bias in the field of tourism has been analyzed in relation to tourist behaviors. More specifically, it has been reported that an individual’s perception of risk may have a relative nature in relationships with others, and people generally tend to perceive that others are at higher risk than themselves, and most tourists are likely to judge their home country to be safer than others’ home countries [27].

- In health-related fields, the concept of optimistic bias has been used in domestic studies on HIV [16-18], cancer [14,15], general health problems [28], and COVID-19 [20-22], and in a foreign study on diseases and smoking [29]. A previous study reported that optimistic bias in health-related fields was found to be a variable that negatively affects risk preventive behaviors [7]. In addition, a previous research on COVID-19 recently found a negative association between optimistic bias and infection prevention behavior [21]. While there are positive evaluations of this concept regarding the fact that it can provide a sense of safety in daily life and have a positive effect on mental health [30], optimistic bias has also been shown to have negative aspects such as leading people to neglect the management of their health and not to perform preventive behaviors or adhere to medical prescriptions [12].

- 2. Identification of the attributes of optimistic bias

- The attributes of optimistic bias were examined through the review of 19 articles (Appendix 1). The list of the tentative attributes of optimism bias is presented below (Table 2).

- ① To tend to underestimate personal risks [A01, A19].

- ② To believe without specific grounds that negative events will not happen [A02, A12].

- ③ To consider oneself less susceptible to risks than others [A02, A05, A09].

- ④ To perceive that negative events will happen not to oneself but to others [A02].

- ⑤ To underestimate the likelihood of negative events [A16].

- ⑥ To perceive that society-level risk is higher than individual-level risk [A08].

- ⑦ To view oneself from a more advantageous viewpoint than others [A02, A09, A17].

- ⑧ To tend to overestimate the likelihood of positive events [A16].

- ⑨ To perceive that there is no individualized risk [A12].

- As a result of comprehensively reviewing the list of tentative attributes, the defining attributes of optimistic bias were identified as follows (Figure 2).

- (1) Underestimation of personal risks ① ⑤ ⑥

- (2) Vague confidence ② ③ ④ ⑦

- (3) Positive future prediction ⑧

- (4) Lack of risk recognition ⑨

- 3. Construction of a model case of the concept

- A model case is constructed as a real case that contains all the identified attributes of a concept but does not include the attributes of any other concept [23].

- Ms. A, a 35-year-old woman, went to the public health center for medical tests due to symptoms of severe dryness, polyuria, and polyphagia a while ago. After she underwent blood and urine tests, her HbA1C level was found to be 12%, and she was diagnosed with diabetes and prescribed diabetes medications. Although she heard about diabetes, she was not well aware of diabetes, so she thought, “If I just take medications for a few days, I will get better,” and she continued to have an irregular lifestyle, lived with severe stress, and did not eat properly (attributes 1 and 2). Although she had heard from people around her that people with diabetes may need to have their legs amputated or many of them suffer from complications of diabetes, but she dismissed such serious complications of diabetes as irrelevant to her (attribute 2). Thus, while taking diabetes medications, she consumed alcohol and instant foods, and drank 5 cups of instant coffee mix a day, not accurately recognizing her disease and thinking vaguely, “How could anything bad happen to me?” (attributes 1 and 4) Some days, she found herself constantly looking for and drinking water like a hippopotamus, and there were a few times when she felt dizzy at dawn, but she dismissed it as nothing serious (attribute 4). Then one day, she passed out and was rushed to the emergency room. Immediately after she was admitted to the hospital, she underwent a blood sugar test and found that her self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG) level was over 600 mg/dl. The cause of her fainting was shock due to high blood sugar, and the endocrinologist recommended that she should be hospitalized and undergo detailed medical tests. However, Ms. A said that she just passed out temporarily due to dizziness and thought positively that she would get better soon as she had done before, and after refusing hospitalization, she signed a self-discharge against medical advice form and was discharged (attributes 1, 3, and 4).

- This model can be seen as an example of a model that includes all the attributes of optimistic bias: vague confidence in oneself, positive future prediction, underestimation of personal risks, and lack of risk recognition.

- 4. Development of additional cases of the concept

- A borderline case is a case that does not include all the attributes presented in the model case, but includes only some of the important attributes of the concept [23].

- Ms. B is a 48-year-old woman who usually has a mild cough and occasionally suffers from shortness of breath. Although she had smoked intermittently since she was young, she did not think of her symptoms as a direct result of smoking. When her symptoms got slightly worse recently, she thought that she would get better only by paying a little more attention to her health (attribute 3). She underwent a pulmonary function test during a free health checkup at a local public health center, and the test results showed low levels of respiratory function that were close to the normal ranges. The doctor warned Ms. B that the test results could indicate an early sign of COPD, but she did not think that her condition was serious enough to be diagnosed with COPD (attribute 1).

- Although the doctor recommended that she quit smoking and exercise regularly, she did not attempt to make any major lifestyle changes. She continued to smoke casually if not heavily every weekend at gatherings with friends, and did not seriously consider her health condition due to the lack of proper recognition of the risks she felt in her daily life (attribute 4). One day, while taking a long walk with her family, she unexpectedly experienced severe shortness of breath. This incident was a very shocking experience to her, and made her think again about COPD. Afterwards, she decided to manage his health more actively, participated in a smoking cessation program, and began to perform regular exercise.

- This borderline case shows the process in which Ms. B, who exhibited only some of the key attributes of optimistic bias, came to realize the importance of changing lifestyle habits through early recognition of the risk of disease. This case emphasizes the importance of recognition of the early signs of COPD and an early intervention for the disease, and clearly demonstrates the importance of individuals’ recognition and behavioral changes in disease management

- This model is a case that does not include ‘vague confidence’, a major attribute of optimistic bias. This borderline case accentuates the importance of recognition of early signs and an early intervention for COPD. The case of Ms. B highlights the importance of individuals’ recognition and behavioral changes in disease management, and in particular, it should be noted that this case does not include ‘vague confidence’ among the attributes of optimistic bias. This case includes some of the major attributes of optimistic bias associated with COPD, and it also illustrates early disease recognition and the process in which the recognition leads to the active modification of lifestyle habits.

- A contrary case is a case that exhibits none of the attributes of the concept and includes the opposite characteristics of the identified attributes of the concept [23].

- Ms. C is a 60-year-old woman and was diagnosed with diabetes 10 years ago, and the only method she used to treat diabetes was to take prescribed medications. She got a minor injury by accidentally cutting her finger with a knife while working at the factory. Because it was not a serious injury, she sterilized the wound at home. After about a week, she suddenly developed a fever, suffered from severe abdominal pain, and felt dizzy, so she hurriedly went to the emergency department of a hospital. Because COVID-19 was rapidly spreading in Korea, the emergency departments of hospitals were reluctant to admit or treat patients with fever, so she had to visit several emergency departments before getting treatment. While moving from hospital to hospital, she felt scared, thinking about even the possibility of death in the car (opposite of attribute 3). Finally, she received tests at one hospital and was diagnosed with sepsis, so she received treatment for sepsis, but she felt anxious that her health would not recover easily due to diabetes complications (opposite of attribute 3). However, fortunately, she was able to regain her strength after surgery. After she almost died of sepsis, she lived a new life again with changes in her attitude toward health. During her hospitalization, she saw many patients around her. She saw many patients with diabetes, including a young 25-year-old patient who was receiving treatments to manage blood sugar levels and on medical nutrition therapy due to uncontrolled blood sugar levels, and a patient who had suffered from diabetes for a long time and was on dialysis due to chronic renal failure. Watching the patients, she thought to herself, “Diabetes is a scary disease. If I don’t actively receive treatment, I will probably suffer like the patients here during the remaining years of my life! (opposites of attributes 1, 3, and 4) I need to be aware of the risks, properly manage my health, and try to control my blood sugar levels from now on (opposite of attribute 4).” She also started to change lifestyle habits beginning with minor ones. She actively participated in dietary education throughout her hospitalization, and even after she got discharged from the hospital, she tried to maintain a healthy life by adjusting her diet and performing therapeutic exercise to control her blood sugar levels at home.

- This model is a case that includes the opposites of the attributes of optimistic bias. The case of Ms. C includes the characteristics contrary to the defining attributes of optimistic bias and emphasizes the importance of realistic perception of risk and active management of one’s health.

- A related case is a case that is related to the concept analyzed but does not contain its important attributes. In other words, it is a case similar to the concept analyzed in some aspects, but careful observation reveals that it has a different meaning from that of the concept analyzed [23].

- Mr. P is a 30-year-old man who was recently diagnosed with hypercholesterolemia. His total cholesterol level was significantly higher than the recommended level. The doctor recommended improving lifestyle habits through changes in eating habits and regular exercise, and advised him to consider drug therapy if necessary. Although he was diagnosed with hypercholesterolemia, he did not make any efforts to improve his eating habits. He continued to maintain unhealthy eating habits, saying, “I can’t give up eating foods I like.” Moreover, although he was aware of the importance of regular exercise, he did not try to start performing exercise using his busy daily life as an excuse. He didn’t make any active effort to perform exercise, thinking, “Even if I start exercise later, there wouldn’t be any problems.” In addition, when the doctor mentioned the possibility of pharmacotherapy, he showed a skeptical attitude toward drug therapy, saying, “I don't want to depend on medications.” He wanted to resolve health problems only in natural ways. Rather than carefully considering his health condition, he made light of his current health problems with an optimistic attitude, and thought, “I am young, so I would not have any serious health problems.”

- The case of Mr. P is not a direct example of optimistic bias but a related case that shows an attitude of indifference and avoidance toward health problems. This case shows that even if an individual does not have optimistic bias toward diseases, he or she may ignore health problems rather than actively dealing with them.

- 5. Antecedents and consequences of the concept of optimistic bias

- Risk perception is an individual’s subjective judgment about the characteristics of risk or risk itself, and is formed by an individual’s experience or social influence. These characteristics of risk perception are related to the fact that optimistic bias is formed through differences in perceptions of risks to oneself, to the society, and to the third party.

- As an individual’s subjective psychological factor, self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in their ability to escape from a particular risk, and acts as a psychological mechanism for oneself. In other words, self-efficacy decreases one’s perception of risk to oneself rather than to others, and consequently increases the difference between the perception of risk to oneself and the perception of risk to others, which may lead to the increase of optimistic bias.

- Risk controllability refers to the degree to which an individual can control a particular risk that he or she encounters through his or her efforts. While individuals perceive a relatively low risk in situations where they can control risks on their own or with the help of others (e.g., driver accidents), they tend to perceive a higher risk in situations where they have little or no control over risks (e.g., passenger accidents). Previous studies have reported that risk controllability reduces optimistic bias mainly by decreasing the impact of optimistic bias on the individual’s own risk perception. Risk controllability and self-efficacy have been investigated as important concepts that can influence behaviors such as behaviors to avoid physical health risks, health-promoting behaviors, and effort to restore poor health status to a healthy state.

- (1) Anxiety reduction [A16]

- (2) Provision of psychological stability [A14]

- (3) Negative consequences for preventive health behaviors [A12]

- (4) Lack of attention to risk-related information [A11]

- (5) Negative consequences for self-protection behaviors [A04]

- 6. Empirical referents

- Empirical referents are the measurable aspects of a concept by which you can recognize the defining attributes of the concept, and they indicate the occurrence of the concept in the field. Based on the identified attributes of optimistic bias, the empirical referents of optimistic bias were identified as follows.

- (1) Underestimation of personal risks: poor health behaviors and accepting objective information in a distorted way

- (2) Vague confidence: increased motivation, anxiety reduction, and increased self-esteem

- (3) Positive future prediction: psychological stability, stress reduction, and positive attitudes

- (4) Lack of risk recognition: overlooking risks, lack of self-protection behaviors, and lack of attention to risk-related information

Results

1) Dictionary definition

2) Scope of the uses of the concept of optimistic bias

(1) Use of the concept in other fields of study: Use of the concept in various fields

(2) Uses of the concept in nursing research

1) List of tentative criteria

2) List of defining attributes

1) Borderline case

2) Contrary case

3) Related case

1) The antecedents of optimistic bias identified in this study are as follows (Figure 2).

(1) Risk perception [A03, A05, A10]

(2) Self-efficacy [A06, A07]

(3) Risk controllability [A06, A15, A18]

2) The consequences of optimistic bias identified in this study are as follows (Figure 2).

- A literature review showed that the concept of optimistic bias is closely related to health behaviors. However, in several previous studies, slightly different terms for the concept, including ‘optimism bias’ and ‘optimistic bias’, were used, and a clear conceptual analysis of optimistic bias toward disease has not yet been conducted. Thus, this study attempted to identify the attributes of optimistic bias and define the concept through the steps of concept analysis proposed by Walker & Avant. More specifically, this study sought to understand optimistic bias by clarifying the concept of optimistic bias, and present basic data for nursing interventions through a clear understanding of the optimistic bias held by nursing care recipients. The attributes of optimistic bias identified in this study are expected to contribute to understanding the optimistic bias of nursing care recipients in the field of community nursing practice and performing health behavior interventions for them. The results of concept analysis through a literature review revealed that underestimation of personal risks, vague confidence, positive future prediction, and lack of risk recognition are the defining attributes of optimistic bias. As for the antecedents and consequences of optimistic bias, risk perception, self-efficacy, and risk controllability were identified as the antecedents of optimistic bias, and based on the identified antecedents, anxiety reduction, providing emotional stability, negative consequences for preventive health behaviors, lack of attention to risk-related information, and negative consequences for self-protective behaviors were identified as the consequences of optimistic bias.

- Optimistic bias has been found to serve as an internal reference point when an individual makes a decision on whether to adopt health behaviors [22]. A previous study reported that individuals evaluate health information and decide whether to adopt health behaviors through optimistic bias [A06]. As shown in several previous studies, optimistic bias has a significant impact on health promotion, prevention, and behavioral change programs [31]. Previous studies have demonstrated that optimistic bias influences the practice of health-promoting behaviors. In particular, Weinstein [7] claimed that optimistic bias acts as a variable that hinders risk prevention behaviors. In addition, according to a previous study, a higher level of optimistic bias is linked to lower levels of lifestyle habits, self-actualization, and health-promoting lifestyle habits [32]. Optimistic bias has also been shown to have a negative association with infection prevention behaviors [21]. Moreover, the concept of optimistic bias has been reported to act as an important obstacle to the recognition of personal risk not only for healthy people but also for patients with diseases [33]. As described above, it has been confirmed that optimistic bias affect the practice of health-promoting behaviors [34]. In addition, a prior study [35] focused on optimistic bias as an internal psychological variable that hinders adherence to health behaviors, and found that stronger optimistic bias was associated with a lower likelihood to adhere to or practice health behaviors. These research results are consistent with the claim of Weinstein [36], who conceptualized optimistic bias as a psychological factor that hinders individuals from deciding to practice health behaviors, as well as the results of previous studies that support Weinstein’s argument. Therefore, there is a need for interventions to correct this optimistic bias to promote adherence to health behaviors needed for disease prevention and treatment. Interventions to reduce optimistic bias are expected to help nursing care recipients to understand their optimistic bias in the field of nursing practice and improve their health behaviors through an education program on the risk of diseases [35].

- It has been shown that optimistic bias is closely related to health-related behaviors and affects the health belief model (HBM) [37]. In light of such research findings, it is thought that understanding optimistic bias will help to effectively understand and apply the health belief model of patients in the field of nursing practice, and thereby it will contribute to promoting individuals’ behavioral changes for healthy behaviors and maintaining healthy lifestyle habits for a long-term period.

- The attributes, antecedents, and consequences of optimistic bias identified in this study as well as other research results are expected to contribute to a more realistic understanding and improvement of the health behaviors of nursing care recipients in the field of nursing practice, and help to encourage individuals to adopt healthy lifestyle habits. Based on research results, the specific suggestions of this study are as follows. First, it is necessary to assess the level of optimistic bias of individual nursing care recipients through personalized health counseling, and offer counseling based on the assessment results of their optimistic bias. In addition, there is a need to eliminate optimistic bias associated with the lack of risk recognition by designing and implementing a risk recognition promotion program. Additionally, it is also necessary to develop strategies for promoting preventive health behaviors. These strategies should include activities that minimize the negative effects of optimistic bias and promote positive behavioral changes, and it is important to raise awareness of the importance of self-protective behaviors and the benefits of adopting healthy lifestyle habits. In clinical practice, these recommendations are expected to help nurses to more effectively understand and manage the optimistic bias of nursing care recipients, which will eventually help nursing care recipients to evaluate their health more realistically and adopt healthy lifestyle habits

- Regarding the limitations of this research, the present study conducted a literature review based on accessible research papers, excluding theses and dissertations, so it is difficult to say that this work has comprehensively analyzed all researches on optimistic bias. In particular, there is a possibility that important papers dealing with the defining characteristics of optimistic bias were not included in this study. Therefore, these limitations should be taken into consideration in generalizing or interpreting the results of this study. Nevertheless, this work is believed to be a meaning research attempt in that this study has contributed to increasing the understanding of optimistic bias and providing a theoretical basis for it.

Discussion

- This study is expected to contribute to gaining a better understanding of optimistic bias. Since optimistic bias causes people to underestimate the risks of behaviors that may have harmful effects on their health, it may hinder individuals’ adoption and maintenance of healthy lifestyle habits, which may have a negative impact on the prevention and management of diseases. Therefore, interventions based on an accurate understanding of optimistic bias can play an important role in improving strategies for the prevention and management of diseases. This research is expected to contribute to exploring more effective approaches to disease prevention and management, and is expected to help to prevent diseases and protect and promote public health in nursing practice and in the community.

Conclusions

-

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

Funding

None.

-

Authors’ contributions

Miseon Shin contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, visualization, writing-original draft, review & editing, investigation, resources, and validation. Juae Jeong contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, visualization, writing-original draft, review & editing, investigation, and resources.

-

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

NOTES

Acknowledgments

- 1. Cho KS. Current status of non-communicable diseases in the Republic of Korea. Public Health Weekly Report. 2021;14(4):166–177.

- 2. World Health Organization. The top 10 cause of death [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

- 3. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. National Health Survey Results Presentation 2022 [Internet]. Seoul: Statistics Korea. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 28]. Available from: http://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/sub04/sub04_04_03.do

- 4. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. 280,000 deaths from chronic diseases in 2022, with medical expenses amounting to 83 trillion won [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.kdca.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501010000&bid=0015&act=view&list_no=724036#

- 5. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Status and issues of chronic diseases in 2021 [Internet]. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency; 2021 Nov 19 [cited 2023 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.kdca.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501010000&bid=0015&list_no=717581&cg_code=&act=view&nPage=1

- 6. Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health-problems. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1982;5(4):441–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/Bf00845372ArticlePubMed

- 7. Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39(5):806–820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.806Article

- 8. Tyler TR, Cook FL. The mass media and judgments of risk: Distinguishing impact on personal and societal level judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47(4):693–708. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.4.693Article

- 9. Park T, Ju I, Ohs JE, Hinsley A. Optimistic bias and preventive behavioral engagement in the context of COVID-19. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2021;17(1):1859–1866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.06.004ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Masiero M, Lucchiari C, Pravettoni G. Personal fable: optimistic bias in cigarette smokers. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction. 2015;4(1):e20939. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.20939ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Hwang YI, Park YB, Yoon HK, Kim TH, Yoo KH, Rhee CK, et al. Male current smokers have low awareness and optimistic bias about COPD: Field survey results about COPD in Korea. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2019;14:271–277. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.s189859ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Weinstein ND, Marcus SE, Moser RP. Smokers' unrealistic optimism about their risk. Tobacco Control. 2005;14(1):55–59. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2004.008375ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Bae BJ. Effect of health news consumption on unrealistic optimism toward cancer risk. American Communication Journal. 2015;17(2):38–52.

- 14. Sohn YK, Lee JW, Jang JY. A study on the persuasive effects of cervical cancer screening prevention campaign - Focusing on mediating and moderating effect of optimistic bias. Advertising Research. 2011;(90):99–131.

- 15. Aiken LS, Fenaughty AM, West SG, Johnson JJ, Luckett TL. Perceived determinants of risk for breast cancer and the relations among objective risk, perceived risk, and screening behavior over time. Women's Health (Hillsdale, NJ). 1995;1(1):27–50.

- 16. Seo MH. A study on the effectiveness and sustainability of an HIV/AIDS human rights education of nursing students: Focusing on knowledge, fear, personal stigma related HIV/AIDS, and stigma communication. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society. 2023;24(6):196–205. http://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2023.24.6.196Article

- 17. Cha DP. Self-serving bias for HIV/AIDS infection among college students. Journal of Public Relations. 2004;8(1):137–160.

- 18. Kim BC, Choi MI, Choi YH, James M. Cultural difference study on optimistic bias of AIDS : Comparison between Korea and Kenya. The Korean Journal of Advertising. 2007;18(1):111–130.

- 19. Jeong YJ, Park JH. The effects of the stroke on the health knowledge, optimistic bias and health-promoting lifestyle in middle-aged adults. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society. 2016;17(9):141–155. http://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2016.17.9.141Article

- 20. Jo SA. Effects of optimistic bias in risk perception of COVID 19 on tourism intentions of potential tourists: Focusing on moderating effects of optimistic bias. Journal of Tourism Management Research. 2021;25(3):523–542. Article

- 21. Wise T, Zbozinek TD, Michelini G, Hagan CC, Mobbs D. Changes in risk perception and self-reported protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Royal Society Open Science. 2020;7(9):200742. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200742ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Chen S, Liu J, Hu H. A norm-based conditional process model of the negative impact of optimistic bias on self-protection behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in three Chinese cities. Forntiers in Psychology. 2021;12:659218. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.659218ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2005. 249 p.

- 24. NAVER. Naver dictionary [Internet]. Seongnam: NAVER. 2023 [cited 2023 Jun 10]. Available from: https://ko.dict.naver.com/#/search?query=%EB%82%99%EA%B4%80%EC%A0%81%20%ED%8E%B8%ED%96%A5

- 25. Suh MS, Suh KH, Kim IK. Relationships between factors from the theory of planned behavior, optimistic bias, and fruit and vegetable intake among college students. Korean Journal of Health Psychology. 2019;24(1):191–208. https://doi.org/10.17315/kjhp.2019.24.1.009Article

- 26. Chapin J, de las Alas S, Coleman G. Optimistic bias among potential perpetrators and victims of youth violence. Adolescence. 2005;40(160):749–760. PubMed

- 27. Larsen S, Brun W. ‘I am not at risk–typical tourists are’! Social comparison of risk in tourists. Perspectives in Public Health. 2011;131(6):275–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913911419898Article

- 28. Hoorens V, Buunk BP. Social comparison of health risks: Locus of control, the person‐positivity bias, and unrealistic optimism1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1993;23(4):291–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01088.xArticle

- 29. Arnett JJ. Optimistic bias in adolescent and adult smokers and nonsmokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(4):625–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00072-6ArticlePubMed

- 30. Perloff LS. Social comparison and illusions of invulnerability to negative life events. Coping with Negative Life Events: Clinical and Social Psychological Perspectives. 1987;217–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9865-4_9ArticlePubMed

- 31. Avis NE, Smith KW, McKinlay JB. Accuracy of perceptions of heart attack risk: What influences perceptions and can they be changed? American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79(12):1608–1612. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.79.12.1608ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Kim SI, Yang SJ. Effect of optimistic bias on perceived health risk and health promotion lifestyle of middle-aged physical activity participants. The Korean Journal of Physical Education. 2019;58(4):87–99. https://doi.org/10.23949/kjpe.2019.07.58.4.6Article

- 33. Masiero M, Riva S, Oliveri S, Fioretti C, Pravettoni G. Optimistic bias in young adults for cancer, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases: A pilot study on smokers and drinkers. Journal of Health Psychology. 2018;23(5):645–656. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316667796ArticlePubMed

- 34. Chu YR, Park JY, An HS, Bae KE. Influence of cognition and optimistic bias on the intention to visiting obstetrics and gynecology of women college students. Korean parent-child health journal. 2019;22(1):22–29.

- 35. Suh KH. Verification of a theory of planned behavior model of medication adherence in Korean adults: Focused on mederating effects of optimistic or present bias. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1391. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-39206/v1ArticlePubMedPMC

- 36. Weinstein ND. Why it won't happen to me: Perceptions of risk factors and susceptibility. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology. 1984;3(5):431–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.3.5.431ArticlePubMed

- 37. Ku YH, Noh GY. A study of the effects of self-efficacy and optimistic bias on breast cancer screening intention : Focusing on the Health Belief Model(HBM). Ewha Journal of Social Sciences. 2018;34(2):73–109. http://doi.org/10.16935/ejss.2018.34.2.003Article

REFERENCES

Appendix

Figure & Data

References

Citations

KACHN

KACHN

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite